Navigating the FDA medical device approval process is a make-or-break journey for any medical device company. It all boils down to classifying your device by risk, picking the right regulatory lane—whether that’s a 510(k), De Novo, or PMA submission—and then backing it up with solid proof of safety and effectiveness.

The specific path you take isn't a choice; it's entirely dictated by your device's potential risk to patients.

Your Roadmap for FDA Medical Device Approval

Taking a medical device from a great idea to a market-ready product is a journey filled with regulatory hurdles. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the gatekeeper, making sure every single product, from a simple tongue depressor to a sophisticated life-support system, is safe and works as intended. This isn't a one-size-fits-all process; it's a structured framework built entirely around risk.

At its core, the FDA's approval system is designed to match the level of regulatory scrutiny with the potential harm a device might cause. This risk-based approach is the foundation of your entire regulatory strategy, influencing everything from the paperwork you'll file to the clinical data you'll need to collect.

Understanding the Three Device Classes

Your first, and arguably most critical, step is figuring out which of the three classes your device belongs to. The FDA has categorized over 1,700 distinct types of medical devices, and your product's classification sets the stage for everything that comes next.

- Class I Devices: These are your low-risk products. Think elastic bandages, surgical scalpels, or hospital beds. They pose minimal potential harm and are subject to the least stringent requirements, known as "General Controls."

- Class II Devices: This is the moderate-risk category. It includes devices like powered wheelchairs, infusion pumps, and surgical gloves. They need to meet General Controls and often "Special Controls," which might mean adhering to specific performance standards or post-market surveillance.

- Class III Devices: Reserved for the highest-risk devices, these products often support or sustain human life, are implantable, or carry a significant risk of injury. Pacemakers, heart valves, and high-frequency ventilators are classic examples.

The device classification isn't just a label; it's the single most important factor determining your path to market. Getting this wrong can lead to serious delays, unexpected costs, and even a flat-out rejection from the FDA.

The Main Regulatory Pathways

Once you have your device's class pinned down, you can map out the correct regulatory pathway. Each one is tailored to a different level of risk and device novelty.

- 510(k) Premarket Notification: This is the most traveled road, used for most Class II devices. The goal here is to demonstrate that your new device is "substantially equivalent" to a legally marketed device (known as a "predicate") that didn't require a PMA.

- Premarket Approval (PMA): The most rigorous pathway, the PMA is mandatory for all Class III devices. This requires you to provide extensive scientific evidence, almost always including clinical trial data, to prove your device's safety and effectiveness from the ground up.

- De Novo Classification Request: What if your device is novel but low-to-moderate risk? The De Novo pathway is your answer. It's for devices that don't have a predicate, allowing the FDA to establish a new classification for them without an automatic (and costly) default to Class III.

To help simplify the complex documentation and stay on top of evolving requirements, many companies are turning to tools like AI chatbots for regulatory compliance. Understanding these fundamental pathways is your first step toward building a successful and efficient regulatory strategy.

FDA Medical Device Regulatory Pathways at a Glance

This table breaks down the primary pathways, linking them to their typical device class and the main goal of the FDA's review.

| Pathway | Typical Device Class | Primary Requirement | FDA Review Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 510(k) Premarket Notification | Class II | Demonstrate Substantial Equivalence (SE) to a predicate device. | Confirm the new device is as safe and effective as an existing one. |

| Premarket Approval (PMA) | Class III | Provide valid scientific evidence of safety and effectiveness. | Evaluate the device's benefits versus its risks. |

| De Novo Classification | Class I or II (Novel Devices) | Demonstrate low-to-moderate risk and establish General/Special Controls. | Classify a new type of device based on its risk profile. |

| Exempt | Most Class I and some Class II | Comply with General Controls but are exempt from 510(k) submission. | Ensure basic quality and labeling standards are met. |

Each of these pathways comes with its own set of requirements, timelines, and costs. Choosing the right one from the start is absolutely essential for a smooth and predictable journey to market.

Finding Your Device Classification and Regulatory Path

The very first step in the FDA medical device approval process is figuring out exactly what the agency thinks your product is. This isn't just a bureaucratic hurdle; it’s the strategic move that dictates your entire path to market. Getting this right from day one can save you from months, or even years, of headaches and unnecessary costs.

Your starting point should always be the FDA's Product Classification Database. This isn’t just a list; it’s a massive library where you can match your device's function and technology to one of over 1,700 existing device types. Digging in here will reveal your device's specific regulation number, a three-letter product code, and, most importantly, its risk class (Class I, II, or III).

Let’s say you’re working on a new electronic thermometer. A quick search for "thermometer" in the database would point you to product codes like "FLL" for a "Thermometer, Clinical, Electronic." This tells you it's a Class II device, which is a huge piece of the puzzle. Instantly, you know you're most likely looking at a 510(k) submission.

The Critical Role of a Predicate Device

For almost all Class II devices, your entire regulatory strategy revolves around one key concept: the predicate device. A predicate is a device that's already legally on the U.S. market, and your job is to prove your new product is "substantially equivalent" to it. This is the whole foundation of the 510(k) pathway.

But finding a predicate isn’t as simple as finding a competitor's product. A valid predicate has to have the same intended use and very similar technological characteristics. If your tech is a bit different, the burden is on you to prove those differences don't introduce new safety or effectiveness concerns.

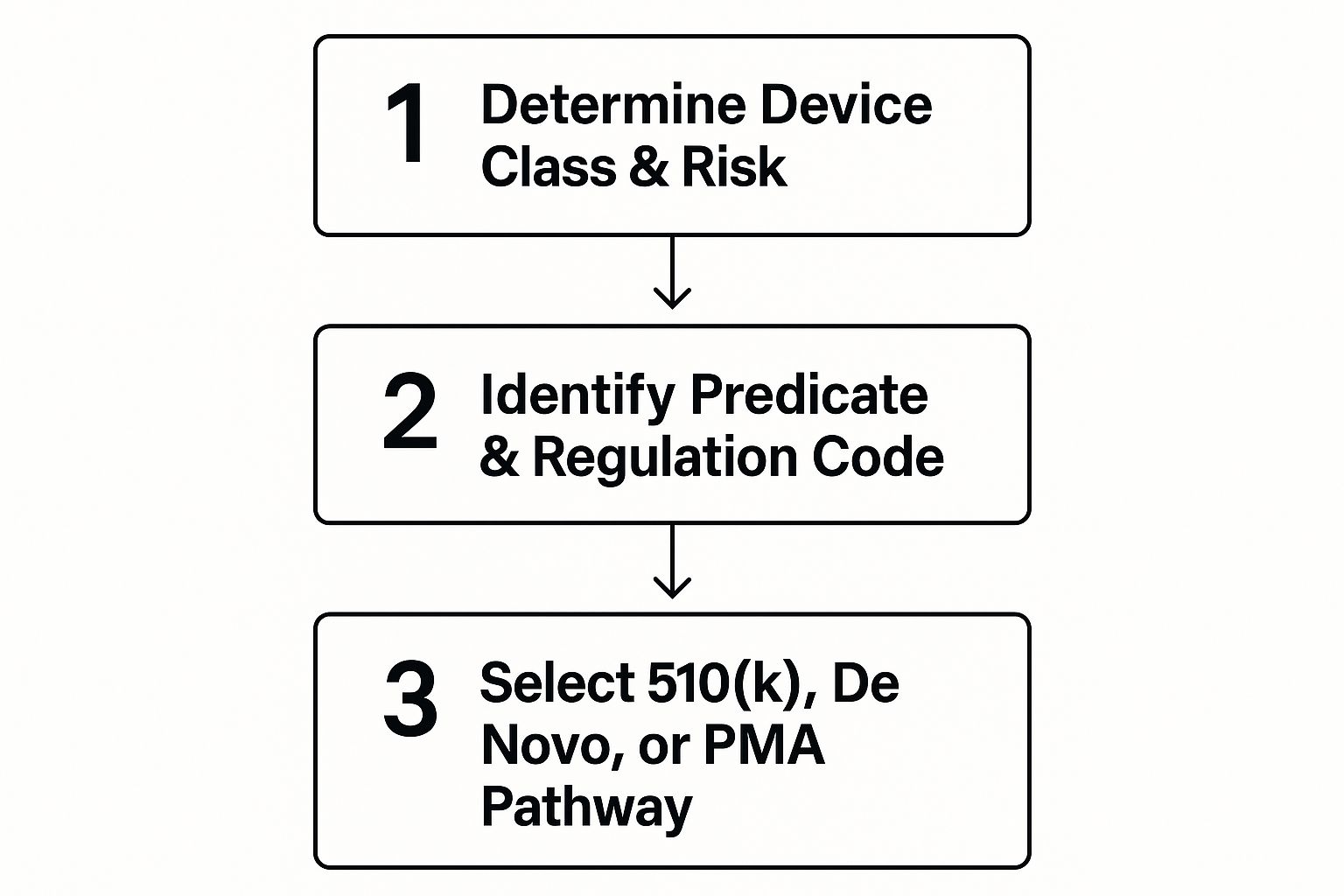

This visual gives you a birds-eye view of how these initial decisions fit together, mapping out the route from risk determination to choosing the right submission.

As the infographic shows, it really boils down to two things: your device's risk level and whether you can find a solid predicate. Those two factors will point you toward a 510(k), De Novo, or the full PMA submission.

So, what if your device is genuinely new? If it's novel but still a low-to-moderate risk, you're probably not doomed to the high-risk PMA pathway. Instead, you'll likely head down the De Novo classification route. This is the FDA's mechanism for classifying brand-new device types that don't have a predicate.

Engaging the FDA Through a Pre-Submission

Feeling a little uncertain about your path? You're not alone. Thankfully, the FDA has a formal program for getting feedback before you sink a ton of money into your official submission. It’s called the Q-Submission program, but most in the industry just call it a Pre-Submission (Pre-Sub).

A Pre-Sub is your chance to have a formal, structured conversation with the FDA reviewers who will eventually see your file. You can ask them directly about your testing plan, whether they agree with your choice of predicate, or anything else about your regulatory strategy. From my experience, it's one of the most powerful tools you have for de-risking the entire process.

"Early interaction with FDA on planned non-clinical and clinical studies and careful consideration of FDA’s feedback may improve the quality of subsequent submissions, shorten total review times, and facilitate the development process for new devices."

– FDA Guidance on Q-Submission Program

Getting ready for a Q-Sub isn't a casual affair. You need to go in with a meticulously prepared package that clearly lays out your case and asks smart, targeted questions.

To get the most out of your Pre-Sub, make sure your package includes:

- A Detailed Device Description: Be crystal clear about what your device is, what it does, and the technology behind it.

- Your Proposed Regulatory Strategy: State your case. Tell them the device class, product code, and predicate you've identified and why.

- Specific Questions for the FDA: This is the most important part. Avoid vague questions like "What do we need to do?" Instead, be specific: "We believe predicate device X is appropriate. Do you agree that comparing its technological characteristics A and B with our device's C and D is sufficient to show substantial equivalence?"

- Supporting Data (If Available): If you have any early benchtop data or other testing results, include them to back up your claims.

A well-executed Pre-Sub gives you invaluable clarity. It either confirms you’re on the right track or flags potential roadblocks while you still have time to pivot. This feedback lets you fine-tune your strategy before committing to expensive testing, dramatically increasing your odds of a smooth review later on.

Getting to Market with a 510(k) Premarket Notification

For most companies with a Class II medical device, the 510(k) pathway is the well-trodden road to the U.S. market. It’s crucial to understand that a 510(k) isn't an "approval" like a PMA. Instead, it's a formal notification where you demonstrate your device is just as safe and effective as a product that's already legally on the market. That single concept is the absolute heart of the process.

At the center of it all is Substantial Equivalence (SE). You don't need to prove your device is a carbon copy of its "predicate" device. What you do need to show is that it shares the same intended use and has similar enough technological characteristics that it doesn’t raise new questions about safety or effectiveness.

This pathway is the backbone of the FDA medical device approval process. And it’s not just for simple devices. Recent data shows that from 2016 to 2024, a surprising 41% of breakthrough-designated devices actually used the 510(k) route. The number of these innovative devices cleared via a 510(k) shot up from just four in 2021 to 17 in 2024. This trend underscores its importance as a faster, less resource-intensive option for many low-to-moderate risk technologies. You can dig deeper into these trends in the full research on recent FDA approval statistics.

Breaking Down Substantial Equivalence

Building a rock-solid case for Substantial Equivalence means creating a meticulous, side-by-side comparison between your device and your chosen predicate. Your 510(k) submission has to leave no room for doubt in the reviewer's mind.

The comparison boils down to three critical areas:

- Intended Use: This one is a deal-breaker. Your device’s intended use must be identical to the predicate's. Even a subtle shift in the target patient group or how it’s used clinically can kill your SE claim and get your submission kicked back.

- Technological Characteristics: Here's where you compare the nuts and bolts—materials, design, power source, and other physical specs. If they're the same, your job is much easier. If they’re different, you have more work to do.

- Performance Data: This is where you close the gap. When your tech isn't identical to the predicate's, you need robust data to prove your device works just as safely and effectively. This could be anything from biocompatibility testing for a new polymer to electrical safety testing for a different power supply.

Let's say you've developed a new handheld ultrasound probe. The predicate device uses a standard piezoelectric crystal, but yours uses a novel, more efficient material. The intended use (diagnostic imaging) is the same, but the technology differs. Your 510(k) would need to be packed with bench testing data showing your probe's imaging resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and durability are as good as or better than the predicate's, all without introducing any new safety risks.

Structuring a Submission to Avoid Delays

A well-organized 510(k) is your best tool for avoiding costly delays. The FDA aims to review submissions within 90 days, but that clock stops cold every time they send you an Additional Information (AI) request. A messy, confusing file is practically an invitation for one.

Think of your submission as a story that logically guides the reviewer to the only possible conclusion: substantial equivalence. You’ll need detailed device descriptions, all proposed labeling, and clear summaries of every performance test you conducted.

The average 510(k) submission has ballooned to over 1,000 pages. This isn’t about just adding volume; it’s about providing enough deep, compelling evidence to answer a reviewer’s questions before they even have a chance to ask them.

To head off an AI request, zero in on the common trouble spots right from the start. Reviewers have a short list of documents they always scrutinize.

Common Pitfalls and Required Documentation

From my experience, I've seen certain parts of a 510(k) trip up manufacturers time and time again. Give these areas extra attention and provide documentation that’s so thorough it preempts any potential questions.

Crucial Documentation Areas:

- Biocompatibility: If any part of your device touches a patient, you need biocompatibility testing data that follows the ISO 10993 standards. Don't just include the results; clearly explain why you chose the tests you did based on the type and duration of patient contact.

- Sterilization and Shelf Life: For any sterile device, you must validate your sterilization method (like Ethylene Oxide or gamma radiation). You also need data supporting the claimed shelf life, proving the packaging will keep the device sterile until its expiration date.

- Software Validation: If your device has any software or firmware, you’re on the hook for documentation that follows FDA guidance. This means providing a software architecture description, a thorough risk analysis, and a complete summary of your verification and validation testing.

I once worked with a company developing a new infusion pump. They picked a solid predicate but didn't adequately document the software validation for their new user interface. Sure enough, the FDA sent an AI request asking for a detailed software risk analysis and full traceability from requirements to testing. That single oversight tacked on more than two months to their clearance timeline, pushing back their launch and messing with revenue forecasts. Proactively tackling these critical areas can make all the difference.

Navigating Premarket Approval for High-Risk Devices

https://www.youtube.com/embed/UxrkmaGRG0k

When your device is in the high-risk Class III category—think pacemakers, artificial heart valves, or other life-sustaining technologies—you've moved beyond the world of "substantial equivalence." This is the FDA's most rigorous tier: the Premarket Approval (PMA) pathway.

This isn't about comparing your device to something already on the market. It's about proving your device's safety and effectiveness from scratch, using a mountain of solid scientific evidence. The PMA application you submit to the FDA is a massive, self-contained scientific report. The agency's expectation is clear: you must provide enough valid scientific data to give them "reasonable assurance" that your device is safe and effective for its intended use.

The Central Role of Clinical Data

The absolute cornerstone of nearly every PMA is robust clinical data. While bench testing and animal studies are critical early steps, for a Class III device, the FDA almost always needs to see how it performs in actual human beings. This is where the journey gets significantly more complex and expensive.

Before you can even start a clinical trial in the U.S., you first have to get an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from the FDA. An IDE is what legally allows you to use your unapproved device in a clinical study to collect that crucial safety and performance data. The IDE application itself is a major undertaking, demanding detailed manufacturing information, all your pre-clinical data, and a meticulously planned clinical protocol.

Your clinical protocol is your roadmap for the entire study. It has to spell out every last detail:

- Study Objectives and Endpoints: What are you trying to prove? What specific, measurable outcomes will you use to make your case?

- Patient Population: Who are the ideal subjects for your trial? Just as important, who will you exclude and why?

- Study Design: This covers everything—the number of patients, the number of clinical sites, and the specific statistical methods you'll use to analyze the data.

For these high-risk devices, extensive clinical trials are almost always mandatory. It can be helpful to see how organizations like ARPA-H are supporting innovators navigating the R&D map towards clinical trials, as this can provide some valuable perspective on getting through this critical phase.

Beyond the Clinical Trial

While clinical evidence is the star of the show, a successful PMA application relies on a strong supporting cast. The FDA review is a comprehensive deep dive that scrutinizes every aspect of your device and your company's operations. This includes an exhaustive look at your manufacturing processes. You have to prove you can consistently build the device to its exact specifications, a process known as manufacturing process validation.

A PMA review is a deep dive into your entire quality system. The FDA will conduct a facility inspection, known as a Bioresearch Monitoring (BIMO) audit, to ensure your clinical trials were conducted properly and that your manufacturing facility complies with the Quality System Regulation (QSR).

This multi-faceted review process means timelines are much longer than for a 510(k). The FDA's own performance goals reflect this. For fiscal years 2025 through 2027, the average total time to a decision for a PMA is approximately 285 days.

Preparing for the Long Haul

Let's be clear: the PMA pathway is a marathon, not a sprint. It demands a massive financial investment and years of effort. Getting through it successfully requires a proactive, strategic mindset from day one.

From my experience, here are a few things that can make all the difference:

- Engage the FDA Early and Often. Use the Q-Submission program. Talk to the agency about your clinical trial design before you enroll a single patient. Getting the FDA’s buy-in on your protocol is one of the single most effective ways to de-risk the entire process.

- Assemble a Cross-Functional Team. A PMA submission is not just a regulatory task. It requires tight, daily collaboration between your clinical, engineering, quality, and regulatory teams to ensure all the pieces come together seamlessly.

- Document Everything Meticulously. I can't stress this enough. From the earliest design napkin sketch to the final clinical study report, maintain impeccable records. During a PMA review, any gap in your documentation can lead to painful delays and very difficult questions from the agency.

Navigating the PMA process is a huge challenge, no question about it. But for truly innovative, life-saving devices, it's the necessary path to bringing that critical technology to the patients who need it most.

Navigating the Frontier: Special Considerations for Novel and AI-Enabled Devices

The world of medtech is buzzing with innovation, especially with the rise of devices powered by artificial intelligence and machine learning. These aren't just minor tweaks to existing products; they're often entirely new technologies that don't fit neatly into the traditional regulatory boxes. This is where the standard FDA medical device approval process gets a lot more interesting.

When your device is genuinely novel, you’ll quickly discover there’s no existing predicate device to compare it against for a 510(k). If it's a high-risk, Class III device, the path forward is clear: a full Premarket Approval (PMA) submission. But what about a game-changing device that is still low-to-moderate risk?

This is the exact scenario the De Novo classification pathway was built for. It carves out a route to market for new, innovative Class I and Class II devices that have no predicate.

When to Pursue the De Novo Pathway

Think of the De Novo process as creating a brand-new regulatory category from scratch. Instead of proving your device is substantially equivalent to something else, you're tasked with demonstrating that it carries a low-to-moderate risk and that general controls (or a mix of general and special controls) are enough to guarantee its safety and effectiveness.

This pathway is tailor-made for devices that represent a significant technological leap. A perfect candidate would be the first-ever diagnostic tool using a completely new biomarker to detect a disease. It has no predicate, but its risk profile might sit comfortably in Class II territory.

To succeed here, your submission needs a rock-solid risk-benefit analysis and a clear proposal for the specific controls that should apply to this new device type. If the FDA grants your De Novo request, they don't just clear your product—they create a new regulation, a new product code, and an entirely new classification.

A successful De Novo submission doesn't just get your device to market. It establishes the very regulatory framework that all future, similar devices—including your competitors'—will have to use as their own predicate. You're literally writing the rulebook.

The Evolving Landscape of AI and Machine Learning

The explosion of AI in medical devices has been nothing short of transformative, creating unique challenges for regulators. The FDA is working hard to adapt its frameworks to oversee software that can learn and change over time, often called Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) with adaptive algorithms.

The numbers really paint a picture. As of August 2024, the FDA has cleared or approved an incredible 903 AI-enabled medical devices. What's telling is that the vast majority—97.1%—were cleared through the 510(k) pathway, with a tiny 2.4% using the De Novo route. This strongly suggests that most AI applications so far are enhancements to existing device types, not entirely new concepts.

The data also shows a heavy concentration in certain fields; radiology applications make up a massive 76.6% of these devices. You can dive into the specifics by reading the full research on AI in medical devices for a clinical specialty breakdown.

For device manufacturers, this brings a few critical points to the forefront:

-

Locked vs. Adaptive Algorithms: Is your AI "locked," meaning it gives the same output every time from the same input? Or is it "adaptive," with performance that evolves as it chews on new data? Locked algorithms are a much cleaner fit for the existing 510(k) or De Novo frameworks.

-

Managing Algorithm Changes: For adaptive AI, the FDA has proposed a "Predicate Change Protocol." The idea is to let manufacturers manage routine algorithm updates without filing a new submission for every single tweak, as long as those changes stay within pre-approved boundaries.

-

Data, Validation, and Bias: Your submission has to be completely transparent about the data used to train and validate your algorithm. This means proving your training data is diverse and truly representative of the intended patient population. Skimp on this, and you risk introducing biases that could seriously impact patient safety and device effectiveness.

Bringing a novel or AI-powered device to market demands a smart, forward-thinking regulatory strategy. It often means more back-and-forth with the FDA through programs like the Pre-Submission, but it’s an essential investment to get these powerful technologies safely into the hands of clinicians and patients.

Common Questions About the FDA Medical Device Process

Trying to get a medical device to market always sparks a lot of questions. The FDA's process is notoriously detailed, so getting clear answers upfront can save you a world of headaches and money down the road. Let's tackle some of the most common questions we hear from device makers.

The big one is always about the timeline. How long does this all take? Honestly, it completely depends on your device's classification and which regulatory path you have to take.

- A 510(k) submission for a Class II device technically has a 90-day review goal set by the FDA. But that clock stops every time the agency asks for more information (which they almost always do). In the real world, you should probably budget for about five months.

- The Premarket Approval (PMA) pathway for a high-risk Class III device is a different beast entirely. The review time alone averages around 285 days, and that's after you've already spent years conducting the necessary clinical trials.

- A De Novo request, used for new, lower-risk devices, has a review goal of 150 days.

What Is a Q-Submission and Do I Need One?

A Q-Submission, or "Q-Sub," is your formal channel for getting written feedback from the FDA before you've submitted your final application. The most popular type is a Pre-Submission (Pre-Sub), which is a fantastic way to ask specific questions about your regulatory game plan.

Is it mandatory? No. Is it a really good idea? Absolutely. We almost always recommend it, especially if you're working with new technology, have a fuzzy predicate, or are just new to the FDA process. It's your single best chance to get the agency's take on your proposed predicate device, testing protocols, or clinical study design.

Think of a Pre-Sub as a strategic alignment meeting with your future reviewer. If you go in with a well-prepared list of smart questions, you can uncover major roadblocks while there's still time to fix them. It's one of the most effective ways to de-risk your entire project.

Can I Change My Device After It Is Cleared?

Yes, but you have to be careful. Any change you make to a device that’s already on the market needs to be evaluated. If that change could significantly impact its safety or effectiveness, you’re looking at a brand new 510(k) submission. This is a critical point where many manufacturers get tripped up.

So, what counts as a "significant" change? The FDA has a whole guidance document on this, but it boils down to a careful risk assessment.

Here are a few examples that would almost certainly require a new 510(k):

- Changing the intended use: Say you have a diagnostic tool cleared for adults, but now you want to market it for children. That’s a new 510(k).

- A fundamental technology shift: If you switch a surgical device’s energy source from radiofrequency to laser, that’s a big deal.

- A major material change: Swapping a patient-contacting material from a well-known stainless steel to a novel polymer? You'll need to submit again.

On the other hand, minor tweaks like changing the device color or a small software patch for a minor bug probably won't require a new submission. Even so, every change has to be meticulously documented in your quality management system. If you're ever on the fence, the safest bet is to talk to a regulatory expert or ask the FDA directly.

At PYCAD, we live at the complex intersection of medical imaging and artificial intelligence. We have deep experience navigating the specific regulatory hurdles for AI-powered medical devices. If you're building a device and need to integrate sophisticated AI, we can help make sure your technology is not just powerful, but also built to withstand regulatory review. Learn how our AI services can move your project forward.